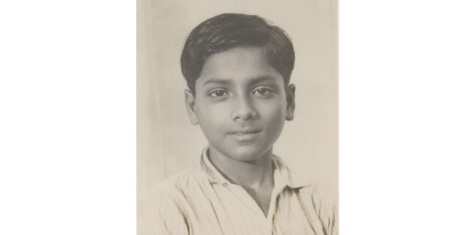

Dialogue with Prithwindra MUKHERJEE – Childhood

Bertrand de Foucauld: “Prithwindra, you were born in Calculta in 1936. At what age did your parents put you in the Sri Aurobindo ashram in Pondicherry?”

Prithwindra Mukherjee: “First observation: it was not our parents who “put” us in the ashram. My father Tejendra was the eldest son of the famous revolutionary Jatindra Nâth Mukherjee, the first deputy of Sri Aurobindo, author of the armed struggle to liberate India. Throughout his journey, Tejendra had maintained contact with the Chef, who had become the Sage of Pondicherry. Invited by Sri Aurobindo in 1947, Tejendra – along with his wife Ushâ Râni – celebrated August 15th in Pondicherry: the 75th anniversary of the birth of Sri Aurobindo would now also celebrate India’s independence day. When I got back to Calcutta, my parents had only one goal: to let us know about this ashram, this corner of paradise on Earth. Welcomed by Sri Aurobindo and the Mother during our visit a year later, we found our real home there. Rothin was thirteen (born February 1934); me, eleven (born October 1936); Togo (native of December 1937).

In Calcutta, glad we had been under our roof, surrounded by the love of our parents and cousins. However, unbeknownst to us, we were bruised by an increasingly harsh socio-political life: V2s crossing the sky; the artificial famine created by Winston Churchill following the Great War; pogrom launched by the Muslim League – in power in Bengal reunified by decree of 1911 – against the defenseless Hindu community; mass flight to Calcutta of Hindu refugees chased in East Bengal which became the eastern wing of the new state of Pakistan; assassination of Gândhi. On the family level, death of Vinodebâlâ Dévi, the beloved aunt of Tejendra (we called her Bordi), precious as a witness and living memory of the spiritual quest of her brother Jatindra; untimely death of Mishti – “Softness” -, our little sister; the ruthless ravage of the polio virus on my lower limbs: I was five years old. My parents had found their consolation with Sri Aurobindo and the Mother[1]Sri Aurobindo’s French companion, Blanche Rachel Mirra Alfassa, nicknamed The Mother, who was to found, in 1968, Auroville: an international pacifist community, North of Pondichery. Cf: From Calcutta to Paris: Prithwindra Mukherjee, the Multi-Dimensions Man, 5th May 2020. Available at: https://contrib.city/index.php/2020/05/05/de-calcutta-a-paris-prithwindra-mukherjee-lhomme-aux-multiples-dimensions/?highlight=M%C3%A8re.

Calcutta had been Jatindra’s field of action and achievement. Housed in the district of Chitpur, with his uncle, a well-known doctor of residents of North Calcutta, enrolled at the University, at the Central College of the North, Jatindra was only eighteen years old when he met Swâmi Vivékânanda , the monk who guided the future of a subjugated people, a people who sought to liberate themselves. Since the end of the 18th century, under the influence of Râmmohun Roy, a wind of renewal has been blowing in this micro-climate of North Calcutta. When we went to a southern district, we used to condescendly announce: “I’m going to Bhavanipur! “

Child of rural Bengal, Jatindra had never forgotten his country of origin: native of the village of Koyâ in Nadiâ, where the ancestors of his mother Sharat Shashi were landowners who also managed the property of the Tagore in Silidah, near Kushtia , territory of Bangladesh since 1971. Less than a hundred kilometers from Koya, lived Umesh Chandra, the father of Jatindra. This scholar in Sanskrit letters was known for his three loves: his land at Sâdhuhâti Rishkhâli, in Jessore, also located in Bangladesh today; his horses; his books. After the heroic death of Jatindra – which we will talk about later – despite having confiscated all of his property, the colonial government had inadvertently left some plots of land: just as the exploitation of some of them brought still a little rent to his family, others were usurped by neighbors who liked litigation and who, having to attend the trials, seemed to know only our address in Calcutta for hospitality. Before going to Pondicherry, we already belonged to three territories: South Calcutta (Ballyganj Place, where my father had built our house), North Calcutta (where members of Jatindra’s maternal family still lived); our ancestral village.

To come back to the question of our “setting in the ashram”, I remember the enthusiasm that had taken hold of us, the three brothers, since our meeting with the Mother and since we had seen Sri Aurobindo. We wanted to be part of this experience with freedom. We were only asked to live this life in joy. Joy, there was at every moment.”

Références