Ile-aux-Moines (Brittany, France): Which Answer To Nature And Man? – Re-ed

Dear Contrib’Citizen,

This summer, the site will offer you to analyze different territories based on water and its use. This last element is prized for its playfulness in France. Its industrial stake unfortunately remains disdained, whether in the maritime domain – while all of France’s marine areas are the second in the world, just after the United States of America – or even in the river sector with a potential that remains underused. Anyway, water, in addition to being a source of life, allows the development of entire sectors such as sport / leisure, tourism and international trade. But this element, and its direct or indirect anthropogenic exploitation, also involves risks: floods (as we have seen in various previous articles) but also erosions. To begin with, the re-edition of the article of last August 18 will allow readers to (re) immerse themselves in this problem of water wear: for the pioneers of contrib.city, a little revision never does wrong!

In the texts to be published next, CC will show examples of erosion from different places: marine environment and river environment. The wear can come either directly from water, or from human activity linked to this resource: for example, a pretty Breton coast will have to both deal with the wear of the waves, especially during storms, and attract tourists who will use the coastal paths themselves. It will also be observed that the failure to take this natural phenomenon into account can lead to risks for human development.

We will see, once again, that the question of floods can completely be coupled with that of a pandemic, as is the case in Mumbay.

Of course, contrib.city would like to suggest avenues of reflection so that we can manage each of our territories well, especially at the local level. The Reply function takes on its full meaning, especially today when we celebrate Human Rights, including Freedom of Expression: each reader is cordially invited to react, to offer their point of view and possible ideas forever more at the same time to use and embellish, in a harmonious way, our Blue Planet. So beautiful, so big and so complex and at the same time so fragile and so small, lost in the Milky Way.

Contrib’City wishes you a good reading and a nice trip!

——————————

Because of its insularity, the Ile-aux-Moines, little territory of only 310 hectares, but with more than 17 km of indented coastline, enjoys a very favorable situation in terms of tourism [1]1. Two sites present well the different touristic attractions of the Ile-aux-Moines (Monks’ Island in French): http://izenahgoud.fr Gilles Arié (formerly the editor of the municipal gazette) and http://www.mairie-ileauxmoines.fr/accueil/decouverte/tourisme but must also plan and invest in order to not to be swallowed up by a harsh nature during out-season, and a tidal wave of visitors in summer-time .

(Cover photo: Port-Miquel, shot from Brouël headland (eastern side): the walls protect from the sea this old neighborhood, located in the heart of the village, BdF, December 29, 2015.)

1. Erosion By Natural Elements

Day after day, at each high tide, the Little Sea (Mor Bihan in Breton), coming from the ocean, cradle of life [2]2. The first forms of life on our planet appeared in the marine environment in the form of unicellular organisms, 4.6 billion years ago, during the Precambian era (-4.6 to -0.570 billion years ago, caresses the shores of the Ile-aux-Moines and bring new lights and poetic contours into the Gulf. Problem: these marine cuddlings, by their salty kisses, or their furious hugs, as during the Wolfgang storm [3]3. The Wolfgang storm has particularly hit the Breton coast with bursts of 51 knots (95 km / h) in the entry of the Gulf of Morbihan, and of 35 knots (65 km /h) inside it in the night of the 29th-30th of July 2019, use the granites, the sandy and earthy layers, in fact everything that forms the ground and that the geographer Jean DEMANGEOT calls pedocenosis [4]4. Pedo, soil and cenose, common: DEMANGEOT Jean, Les milieux “naturels” du globe (The “natural” environments of the globe), Armand Collin, p 4.. This has two consequences: on the one hand, the island area decreases – and the rise in sea level accentuates this tendancy [5]5. Some climatologists predict an average increase in the level of the sea of 1 meter by 2100. – and on the other hand, certain elements of urbanism are found at risk in middle or long term. The typical case is the old house built near the shore with a coast that is getting closer and closer.

But the sea is not the only factor of erosion.

Wind and rain also play an important role in the evolution of the island ecosystem, especially in its built components. Indeed, the terrestrial channels of communication, for the transport of not only the permanent inhabitants or holiday-makers (or the secondary residences dwellers), or the daily visitors, but also for the goods necessary to daily life, represent a vital equipment to the Island. Wind, rain, and thermal erosions [7]Even though the differences in temperature are moderate because we are in an oceanic climate, they still cause dilatation and contraction of the materials that are likely to be driven by the rains. damage roads and paths.

2. Touristic Impacts

If tourism is likely to generate revenues, whose potential is not always exploited at best and not necessarily managed in a very fair way [8]9. The shuttle service between the island and the mainland is the big winner in the Ile-aux-Moines tourism, but the souvenir shops are very much dependent on the weather and the economics, which means that a secondary resident, or a daily visitor, will almost certainly take the shuttle. But nothing can force him to buy a book or a “Breton” bowl., it also leads to the wearing away of green spaces and amenities. Indeed, to natural erosion, one must add the one caused by the passage of people and vehicles. The coastal footpath, for example, is a small track that goes around Ile-aux-Moines (with some interruptions). If it can very well accommodate a few casual walkers, it will not withstand the daily passage of dozens of tourists: the hammering of shoes, the possible use of walking sticks without rubber protections, the alteration of hedges protecting the path from marine winds, rain and erosion, and finally the rejection of waste. One must not forget that a tourist activity necessarily leaves rubbish. The public awareness aims to reduce the presence of the latter but it would be unrealistic to bet on a 100% obedience of walkers to the rules of environmental protection, until proven otherwise. Waste also refers to the management of these discharges, therefore a cost that is mainly borne by the municipality, responsible for site management and ad hoc local development (10. « Entretenir un réseau de sentiers ouverts au public » in Plans de gestion du Conservatoire du littoral – Site des landes et prairies de l’Île-aux-Moines – Morbihan (“Maintaining a network of trails open to the public” in Coastline Planning Authorities – Ile-aux-Moines / Morbihan heaths and meadows zone, CONSERVATOIRE DU LITTORAL, November 2017, accessed 17/08/2019 [Available on:] file: /// C: / Users / Home / AppData / Local / Temp / Site-Management-Plan-of-Landes-and-Meadows-of-Ile-aux-Moines-56-.pdf – cf also: www.conservatoire-du-littoral. fr /, accessed 17/08/2019.)).

3. The Answers

To protect the island from natural erosion, and as we saw above, the Conservatoire du littoral took care to preserve the hedges of the coastal footpath, even if it means to build some when they did not exist, as one can see it on the beach between the islands of Brouel and the Bois de la Chèvre.

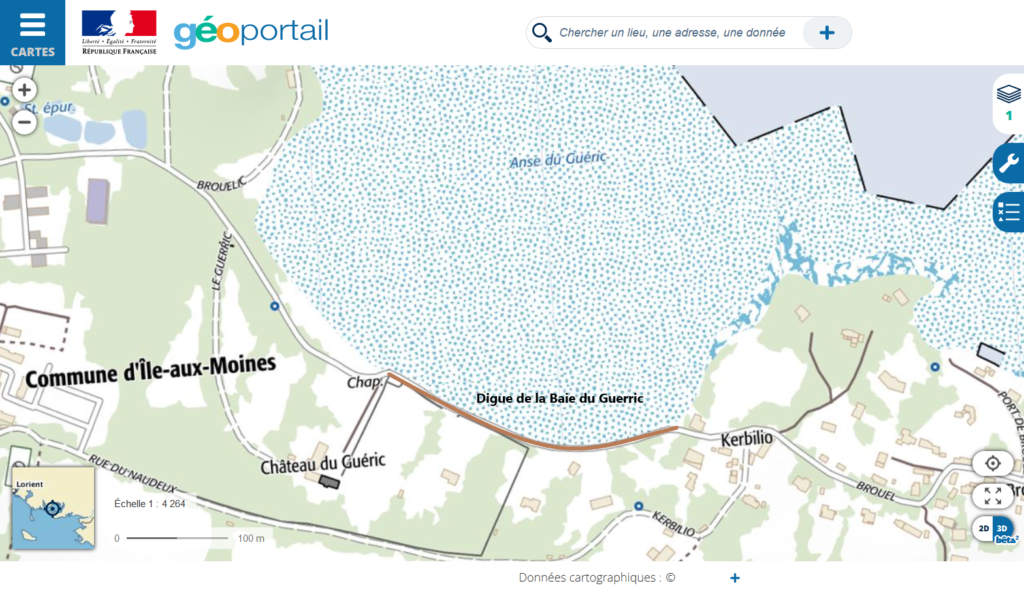

In order to preserve the coastline from the erosion of the sea, stonewalls, veritable sea dikes, were built in the past and still remain today. The wall traversing the Guerric Bay is a perfect example: it protects the beach by preventing it from backing up and the Brouel road which allows the public and vehicles (including delivery or construction trucks) to go from the port to the eastern headland of Ile-aux-Moines. Finally, this development of the coast guarantees the durability of the houses and the chapel located along this stretch of road. As such, the creation of future portions, still to be built, of the coastal footpath can be a good opportunity for planning the coastline and preserve it from marine erosion. Indeed, the construction of a seadike, where possible and geographically relevant, would both offer to visitors a beautiful view of the Gulf, provide a solid, and above all repairable or replaceable, barrier, all by diminishing the intrusive caracteristic that the footpath may represent in some real estates. Without a lack of facilities that allow walkers to go dryfoot, that is to say above the level reached by the sea at high tide, with the highest coefficient, the municipality will have no other choice than to settle the coastal track in the some private properties. Emmanuel Cueff, resident of Ile-aux-Moines, bitterly experienced this bitter when he saw his legal request to circumvent the path rejected by the local Administrative Court (in summary) in August 2010. [9]11. “Coastal Footpath. Judge rejects Emmanuel Cueff’s request” in Le Télégramme, September 3, 2010, [visited on the 17/08/2019]. Available at: https://www.letelegramme.fr/local/morbihan/vannes-auray/cantonvannes/ Île-aux-Moines / coastal path-it-judge rejects request-la-d-emmanuel-Cueff-03-09-2010-1037621.php # hYX7I1pFzUW3AjlK.99

A more peaceful and longer-term solution would be a kind of partnership between the municipality and the landlords to share the construction and management costs of the stone dikes when they are located in the properties and therefore outside the public domain. These dykes would benefit the entire town by avoiding its territory, very exposed to the sea, to reduce and spare it from seeing its amenities, such as the footpath precisely, threatened by natural elements. The lines of communication, and especially the roads, suffer from chaotic management. The secondary D316A road crosses the island from the seaport to the market place. Then the road divides into communal ones and therefore depend on the budget – and the management – of the local Town Hall. These public equipments, a real extension of the island spine that begins with the port and the secondary road, must be considered as priorities to allow the flow of people and goods – and therefore daily life – into the Ile-aux-Moines.

Références