Charles de Foucauld: An Explorer Till The End of His Path

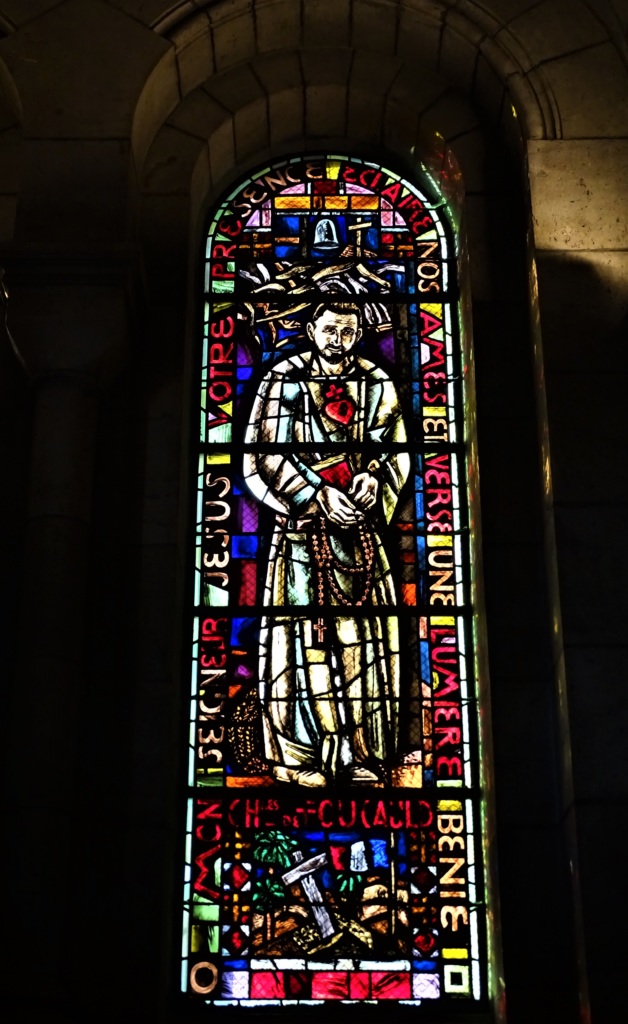

I rarely talk about my family. But the Vatican City’s announcement on Thursday May 28th of the canonization of Charles de Foucauld forces my hand a little, even if it means putting back the articles originally planned for a few days. May the Contrib’Citizen be reassured! I am not going to impose an additional biography of this explorer on them: others have done so, often with great talent[1]BAZIN René, Charles de Foucauld – Explorateur du Maroc, ermite au Sahara, Paris, Nouvelle Cité, rééd 2003 (éd. orig : 1921), 543p. Lire également : SIXT Jean-François, Charles de Foucauld : sa vie, sa voie, Paris, Artège , collection Poche , avril 2016. SIXT Jean-François, Le grand rêve de Charles de Foucauld et Louis Massignon, Paris, Albin Michel, collection Spiritualités , mars 2008. SOURISSEAU Pierre, Charles de Foucauld : 1858-1916 : biographie, Paris, Salvator , collection Biographie , juillet 2016. CHATELARD Antoine, Charles de Foucauld : le chemin vers Tamanrasset, Karthala , collection Chrétiens en liberté , février 2002. CHATELARD Antoine, La mort de Charles de Foucauld, Paris, Karthala, collection Tropiques , novembre 200. , Paris, Grasset, 2014, 521p. However, I want to express what I like about this man.

First of all, Charles was someone who went to the end of his action: for example, during his “party” period, when he organized a reception, the whole city knew it, whether in Saumur or in Pont-à-Mousson (both French military towns)! Or else, while he was in garrison, he had not hesitated to bring his mistress (today one would say “his partner”), via a trunk, into his military barracks; or again, then at the time of the arrests in Saumur, he dressed as a laborer, had easily been able to thwart the sentry of the barracks and go to a reception in Tours, passing by the Police Commissioner who had laughed at his prank. But once arrived at the party place, he was received by his own general, himself invited! Conversely, at another time, he had left his garrison, disguised himself as a beggar and had wandered for several days, living on alms, before being recognized and brought back to his quarters.

Foucauld knew how to adapt to his environment, even if it meant going around obstacles or facing them: for his exploration in Morocco (Recognition in Morocco 1883-1884 [3]), he disguised himself (again!) as a Jewish traveler, knowing that if his true identity as a French Catholic were discovered, he would have been executed by the Muslim authorities. Charles, who was the first European to explore the High Atlas, received the gold medal from the Société de Géographie[2]Located at 184 boulevard St Germain, in Paris, right next to the Institute of Geography of the Sorbonne where I wrote, under the direction of Pr emeritus Michel Carmona, my own thesis, dedicated in particular to Charles, and which focused on among others on the Maghreb or black African families in the deprived North-Eastern part of paris Region, another today’s “periphery” as well as the Academic Palms, awarded in the Sorbonne University, for his work as an explorer[3]de MARIGNAN Jean-François, Sur les pas de Charles de Foucauld (In Charles de Foucauld’s footsteps), [consulted 1st June 2020]. Available at : Sur les pas de Charles de Foucauld..

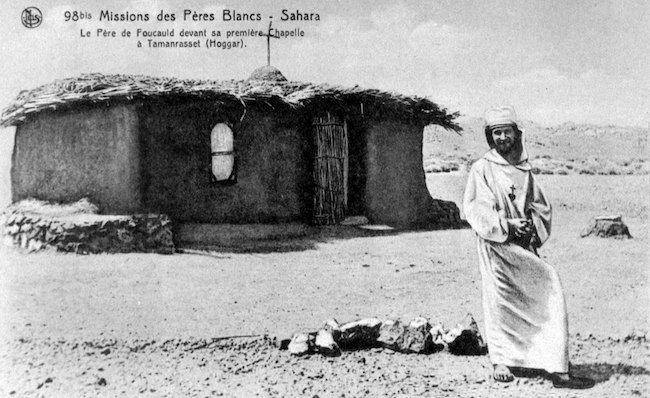

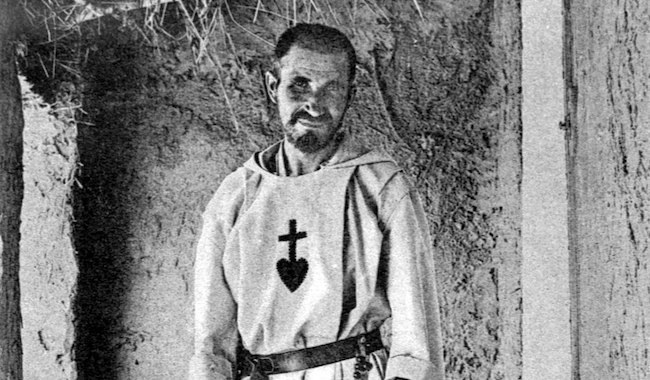

Converted, and after spending a year as a gardener in a convent (one would say today: “after an unpaid international internship with overtime, in the agro sector”), Foucauld left to settle in one of the extremities, probably the poorest and wildest, of the French Empire: the south of Algeria, and more particularly in the Assekrem and Tamanrasset. Contrary to what one can possibly think, Charles led both a hermit’s life (“a break”) but also meetings (“networking”) because “Tam”[4]Tamanrasset nickname is one of the great crossroads of the Sahara. There he met the Tuaregs, whose language and customs he learned there, and wrote a Franco-Tuareg dictionary; but he also maintained links with the metropolitan people, mainly the military, such as General Laperinne[5]The fact that Charles de Foucauld developed links with the French military gave the impression to certain historians that Charles was a spy. Personally, I have no opinion on the question but this idea seems to me rather absurd, given the Father’s own state of life..

I would like to take this opportunity to point out that the Assekrem plateau, surrounded by chimneys and basalt peaks, is considered to be one of the most beautiful places on the globe. The peaks of red rock delight the traveler who has spent his day climbing the massif and finally reaches the hermitage. There is a marvelous view up there, even fantastic, one overlooks a tangle of wild and strange needles, to the north and to the south nothing stops the view: it is a beautiful place to adore the Creator wrote Charles to his cousin Marie Moitessier.

A height that purifies and reveals the fragility and therefore the beauty, the nobility of man. Every man, every woman, every child.

Foucauld evokes for me other characters who have either traveled or shown a similar sensitivity, or who have crossed other deserts. Antoine de Saint Exupéry, almost his contemporary, evokes the poetry of Africa in the Little Prince: I think he took advantage, for his escape, of a migration of wild birds. Or else the hell of aridity, of torrid heat, of thirst, in Terre des Hommes: We believe that man is free … We do not see the rope which connects him to the well, which connects him like an umbilical cord, to the belly of the earth. If he takes one more step, he dies[6]de SAINT-EXUPERY Antoine, Terre des hommes (Wind, Sand and Stars), Paris, Gallimard, 1939, p149 (coll. Folio).. Thirst for meaning and unknown horizons for Charles, the explorer. Quest for an absolute for the philosopher Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt who, gone to write a screenplay about Charles de Foucauld, had lost his way, one night, in the middle of the Hoggar mountains, only to find better himself: I am entering inside the beyond-world […] Dazzling; Flashing […] The more I am progressing, the more the evidence is standing. “Everything has a meaning”. “Felicity”… Fire … A certainty shines above all: He exists [7]SCHMITT Eric-Emmanuel, La nuit de feu (The night of Fire), Paris, Albin Michel, 2015, p137-140 (Coll. Poche). See also: Schmitt.. Thirst for adventures as for Frison-Roche who explored the Hoggar during several of his expeditions [8]FRISON-ROCHE Roger, Appel du Hoggar (Hoggar’s call), Paris, Flammarion, 1935; La piste oubliée (The lost track), Grenoble, Arthaud, 320p. Foucauld, for me, is also linked to Paul Claudel, because of the mystical union between man and nature: How all creation is with God in a deep mystery! exclaims the architect Pierre de Craon, in the piece L’annonce faite à Marie (The Annunciation of Marie)[9]CLAUDEL Paul, The announcement made to Marie, Paris, Gallimard, coll. Folio, 1940, p18.

For a reason that I do not know, Charles also reflects the sensitivity of one of his contemporaries and of whom I am a fervent admirer: Guillaume de Kostrowitzky alias Apollinaire. Even in a geographical place with a lot of water [10]I have written enough articles on the floods of the Seine River in the Paris Region to prove it., the human being remains facing his inner desert, his existential loneliness, his thirst for meaning: As under the bridge/ Of our arms flows/ The exhausted stream of everlasting stares[11]APOLLINAIRE Guillaume, “Le Pont Mirabeau” in Oeuvre Poétiques (Poetic Works) – Alcools, Paris, Gallimard, 1965, p45. Translation: https://lyricstranslate.com. The Sahara also brings me to the peri-urban deserts that Capdevielle evokes in his song: When you are in the desert, For too long, You wonder who it is for, All those a little rigged rules […] Yesterday a man has come to me with a slightly trailing gait, He’s told me how many days you held, I replied: soon 30, I remember he hoped to go up to 40 […] I’ve understood that I could soon regain the city. [12]CADEVIELLE Jean-Patrick, “Quand t’es dans le désert” in Les enfants des ténèbres et les anges de la rue (“When you are in the desert” in Children of darkness and the angels of the street), 1979, CBS Disques. [Accessed May 30, 2020], available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_mRN_iq1-k.

To explain Charles de Foucauld, it should also be remembered that the family cultivates a tradition either of the military (“giving oneself for one’s homeland”) or of a religious one (“giving oneself for one’s God”) for generations, even it means to risk one’s life as a Henri, perfectly German-speaking, by “slamming the door” and treating Renault officials “bastards” during the Franco-Nazi Collaboration then joining the Solognote Resistance[13]The Sologne Region is a forest region, in Central France, just South of Orleans city where he will transport arms, during the Second World War; even if it meant breaking one’s career, as when colonel Camille-Louis de Foucauld, military attaché to the French Embassy in Berlin (a very prestigious post at the time) refused,around 1905, to send the troops to requisition convents and monasteries (it would be a bit like asking today’s soldiers to come and ransack the offices of humanitarian NGOs); Even if it means, finally, like Charles in the XXth century, to offer one’s life for what one believes in, for Whom one believe in, like Armand de Foucauld, massacred with his entire community, in 1792, after leaving the diocese of Arles and “gone up” to Paris to join his archbishop, Jean Marie du Lau d’Allemans.

Charles de Foucauld also evokes, for me, the image of Christian de Chergé and the monks of Tibhirine [14]Les moines de Tibhirine, [consulted June 1, 2020]. Available at: https://www.moines-tibhirine.org / who had voluntarily stayed in their monastery, in order to maintain fraternal links with the inhabitants, and who were murdered in 1996.

Tribute to all the men and women, known or not, who give their lives to go to the end of their path. Tribute to all those who braved, and continue to so, the risks and the grueling work of medical or social care in times of epidemic. Tribute to all those who believe in human beings, in their physical and spiritual essence, and who are ready to testify about them in the deserts and mountains of our urban solitudes.

(Cover photo: Le Hoggar, in front of Charles de Foucauld’s hermitage. April 1978. © CC)

Références